Full disclosure: In many ways, this is not a new book of poems. It’s Les Murray’s first selected poems in fifteen years, and it’s not enormously different from the last one — a shakeup, with a scrambling of different poems throughout — some grand new additions, some beloved verses gone. This is to begin with a small quibble, because the larger message is this: It’s never really a bad moment to come to Les Murray, one of the best poets writing in English now. Like Ted Hughes, Seamus Heaney, Paul Muldoon, and Derek Walcott, he enlarges the project of naming the far-flung corners of a world English has imperfectly attempted to conquer, and of examining the distances that that language travels, all while tracking the music of what he calls home.

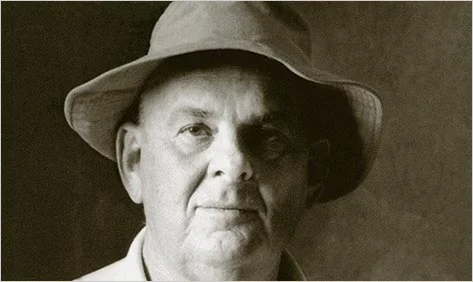

In fact, Murray has stayed in one place much of his life. He is the descendant of Scottish immigrant farmers who worked the backcountry bush province of Bunyah, Australia. He grew up in sharecropping poverty, in a house that sometimes had cracks big enough to let snakes in. When Murray was a teenager, his mother died of a miscarriage. Despite leaving to become educated, Murray moved back home and made a go of the home farm. All this would be beside the point if what Murray has to say of his time and world weren’t said with such flinty, intoxicating music. He takes on sawmill towns and gum forest places and lives whose raw light — however rich — never corresponds to the beauty imagined for the merely scenic. There’s a supple, decentered quality to admire in Murray’s work.

Murray uses the word outlandish more than once in his poems, and perhaps that’s an accurate description, not only of Australia (home of the dingo, the Wang Wauk, the billabong) but of the project of poetry, too. Murray writes a poem recalling his father’s use of the word homely — meant in his dialect to mean comfortable, homelike — and another in praise of pole beans, which he describes alternately as “dolphins at suck” and“misshapen as toes.” That in Murray’s hands something as common as garden beans can grow so strange, sinister, and possibly alien is a tribute to his craft. Indeed, in Murray’s world, many things are alien, not merely the “outlandish” other but also the self, the darkness in which one experiences the “interior.” Not just the continent (a place for “mystic poetry”) but the also self can be wild, unsettling, unknown.

So, too, can the modern world unsettle — the world encroaches and borders the bush. Many ofMurray’s verses are peopled with alien figures, recent technological arrivals, unknowable forces — including, movingly, his son’s autism. Other landscapes Murray depicts pit the uneasily futuristic or destructively recent against the primeval — not a bad way of capturing Australia’s recent settlement and expansion into towering cities but also not a bad way of marking the strange times in which we live. Somewhere between bush and interstellar age, Murray folds his poems together seemingly casually. Sometimes, like boomerangs, they arc outward before spinning into somewhat miraculous reflections. Addressing the homely and also majestic emu, Murray writes:

You’re Quaint, you’re Native,

even somewhat Bygone. You may be let live — but beware: the blank zones of Serious disdain

are often carte blanche to the darkly human.

Murray, who might well be describing poetry’s majestic but surely marginal space, continues:

Heraldic bird, our protection is a fable

Made of space and neglect. We’re remarkable and not;

We’re the ordinary discovered on a strange planet.

Are you Early or Late, in the history of birds

which doesn’t exist, and is deeply ancient?

Are we early or late, in our own ancient history? These are the questions, indeed, to ask of existence as we pass through.

I always welcome the chance to admire Murray. There were poems from other books I missed in here, and some that seemed not to hold the full heft of Murray’s powers. That’s OK: this book was enough to send me back to the others to hunt out what I did love. Because I’m from California, a place with its own weathers that need naming — a place overrun with now-invasive Australian eucalyptus — I read Murray hedged between some ancient bones and a wildly modern kind of life. Reading Murray’s poems, our own oddly non-local eucalyptus seemed more bright, more strange. Murray’s best poems make what’s nearby seem odder, and more alive, too.